Talent Waste

1:14am, 1 October 2013

It’s always struck me as somewhat strange when people in Computing call out our field, arguing that “the best minds of ‘my’ generation are wasting their lives thinking about how to get people to look at more ads.”

Or, as my friends put it: ‘why work for X? What they do is so useless!’

This line of reasoning makes me uneasy. There’s something intellectually snooty about it that I can’t place. When business or engineering students say they want to go into banking, nobody blinks — despite the utter depravity of the field. And when a young man or woman goes into acting, nobody says ‘what a waste of talent!’

(Well, actually they do. But they probably only say that when the model or actress concerned graduated from Harvard Law School or other like University.)

There are a few issues here that get mushed together, whenever we talk about talent and work.

The first is that of potential. If a person graduates from a prestigious university or earns a degree in a ‘difficult’ field, there is some expectation that the person should go on to do Great Things. This higher expectation is a result of the person’s higher perceived potential. There’s nothing wrong there; it’s reasonable to ascribe bigger things to people with great credentials.

But how, then, do we explain the lack of negative judgment when it comes to banking? People with great qualifications have for three decades gone into finance, ostensibly to make a killing. (The only way to become a quant, for instance, is to first earn a few degrees in Physics, Computer Science or Math). And in recent years there has been some blowback to the excesses on Wall Street — see as example this piece by John Cassidy at the New Yorker, which argues that today’s Wall Street is socially worthless.

My friends and I find the idea of being an investment banker socially repugnant, but then again we might simply be at the leading edge of public sentiment. At least, we’d like to think so. But it’s understandable if our disgust isn’t shared by many others: banking has long been regarded as a respectable field, after all — and there are arguments for its social utility.

My question, again remains: during the 1980s, when complex financial instruments were first coming into their own, why did no one say ‘the best minds of my generation are wasting their lives thinking up new derivatives’?

I suspect part of this has to do with compensation. Banking pays well, and it pays consistently. Whereas acting does not pay well for the average actor, and it does not pay at all consistently.

High compensation probably overrides some of our objections to a particular job. Successful actors don’t get grief for ‘wasting’ an MIT degree, after all. (Only unsuccessful ones do). And rich investment bankers don’t — yet — get grief for wasting their potential.

With Internet startups today, however, we have a different story. The payout is similar to Hollywood: a few lucky ones get acquired or IPO and hit the jackpot. But the average startup does not pay well relative to the corporate world, and jackpot-level payouts are inconsistent. It’s easy to get cynical when Silicon Valley is viewed in terms of chasing payouts. It’s also easy to attack people chasing these acquisitions (while working on ‘frivolous’ startups like Youtube, or Zynga) as wasting their potential.

To a certain extent, these attacks are right. It is probably better for society if you work for a company solving meaningful problems. Companies like Google, Lightsail Energy and SpaceX pass this bar. Companies like Zynga, Pinterest, Instagram don’t.

If you think about it, the startups that get pegged as frivolous tend to exist at the intersection of tech and entertainment. They fail the meaning test because they’re not seen as necessary. Whereas the decidedly unglamorous business of manufacturing ball-bearings and car engines get a pass on the meaning test; humanity would be worse off without ball-bearings or cars.

So the question becomes: are companies like Zynga, Valve, Pinterest, and Instagram creating value? One way of arguing this is to do so in terms of economics: they fulfil a demand in the market, therefore they do create value. Maybe they don’t create ‘necessary’ value, but you can’t argue that they’re socially worthless the same way investment banking has become.

However, companies that fall into the same ‘unnecessary’ category: tabloids, lifestyle magazines and the movie and music industries don’t face the same amount of derision. And the reason they don’t, I think, is because they don’t demand high qualifications the way technology startups do.

So here we get to the gist of it: ‘the best minds of my generation’ implies people with high intelligence. And the people with the best intelligence, the argument follows, should spend their God-given gifts working on something of meaning.

(Except when it comes to banking. Because, you know, that pays well).

I realise my objection to this line of reasoning is that it’s so presumptuous. Not to mention prescriptive. The set of socially meaningful activities in the eyes of one person can’t possibly be the same as another’s. You don’t see people advising intelligent young people to pick medicine over advertising, or cancer research over journalism because ‘it has more social value!’. More importantly, it’s unclear what fields deserve intelligent young people working in them.

For example: society would certainly be poorer without movies and music, but it’s not clear how you might compare their value with other industries. Is a music startup creating new lifelines for existing cultural institutions less valuable than startups solving the energy crisis? This question is complicated by the nature of creative destruction: innovative startups tend to look trivial or frivolous at first. Today’s Youtube is tomorrow’s cultural institution. How do you judge value here? The answer is: you can’t.

In computing, as in life, people do whatever they choose to do, and we should be happy so long as they’re creating value in whatever ways they choose.[1]

Now, I suppose my argument applies as generously to Zynga and Pinterest as it does Google and Palantir. I cannot be derisive over the engineers working in the former two companies, or compare them negatively to the people working in the latter two. Doing so requires me to extend my derision to people working in fields like music and movies.[2]

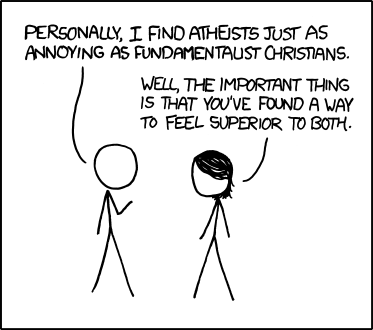

Perhaps this is an instance of a more general rule: when an argument gives you the ability to lord it over some set of people, the argument is probably mistaken.

The way this one certainly is.

Notes

[1] I propose that you’re only allowed to deride people who create negative social value e.g. investment bankers.

[2] That is not to say that you can’t think of ways to increase your value creation. For instance, you might serve with an NGO on the side, or engage in philanthropy. But that is very different from judging and prescribing different levels of meaning in work.

Get updates

I write an essay a week on topics loosely connected to building a technology company in Asia. You may subscribe below for essay updates:

Other essays

The Most Important Class I Took in NUS

Asian universities and the pursuit of truth.

This Strange Thing Called Patriotism

How Malaysian must you be, before you consider leaving the country?

Principles for Technology Choice

I don't have a lot of time to code. Under my constraints, here are some personal principles for picking technologies.